Brain and Building: Finding Miracles Through Digital Twins

by Brianna Grossman

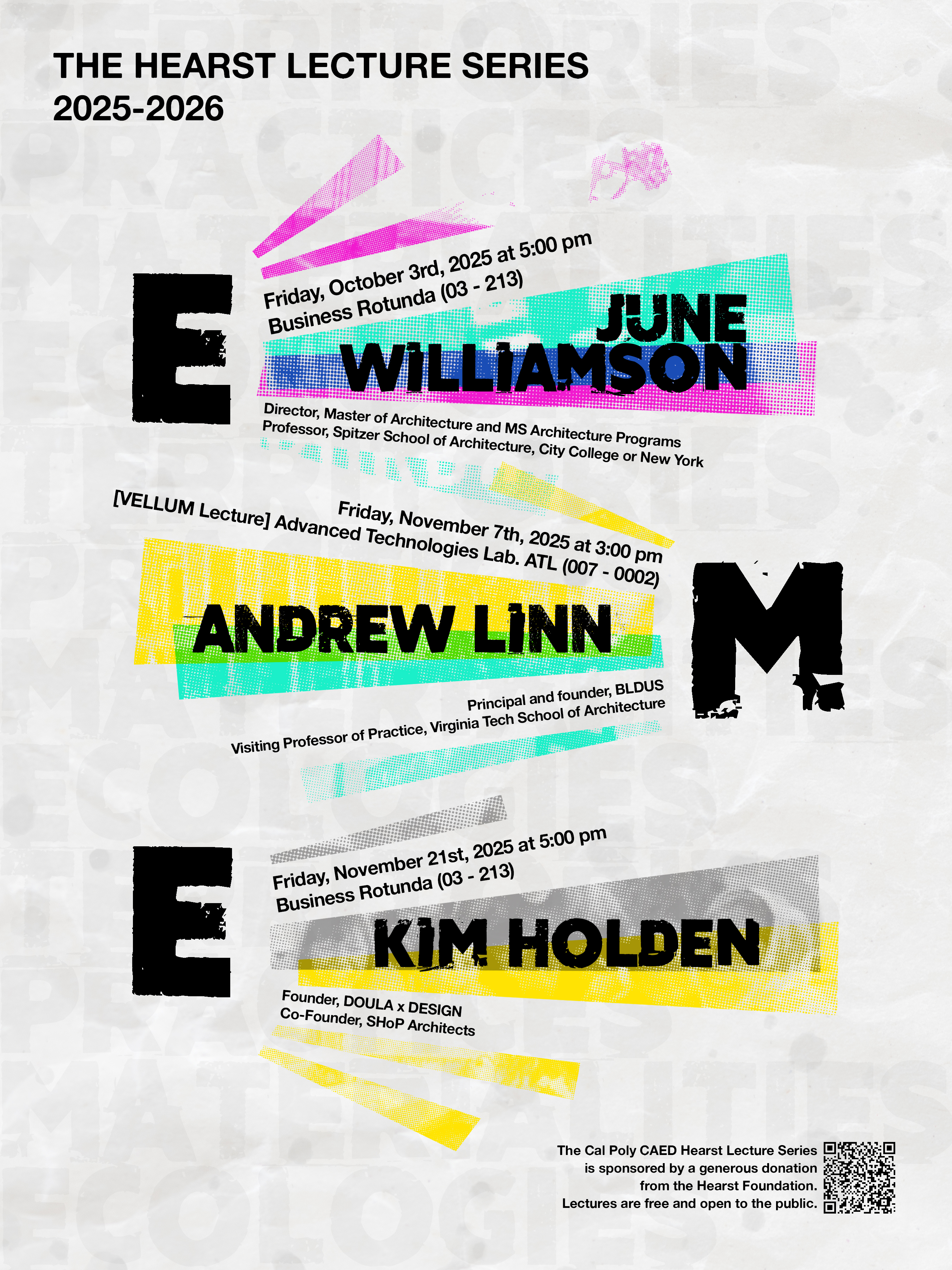

Clockwise:

1) Lukesh in the AR/VR headset running through various simulations

2) Deep brain electrode implants in Lukesh’s head

3) The electrode scars on the back of Lukesh’s head

4) Identified seizures on Lukesh’s brain scans.

Todd Lukesh was in third grade when he realized he wanted to be an architect. From playing with Legos and Lincoln Logs to hauling around T-squares and drafting boards, he had his mind set.

Lukesh suffered from a life-long journey of seizure conditions. They seemed to worsen over time increasingly and required medication until they subsided. Still, the epileptic conditions would return following more head traumas, including one he suffered playing water polo during high school and another when a distracted driver hit him in a head-on collision during college.

He describes his journey with seizures as a rinse-and-repeat cycle.

“The reoccurring theme is that I’d have a head injury, I’d have seizures, they would medicate me for a certain period of time once the seizures were controlled, take me off the medication and then I’d be seizure-free until the next head trauma,” he said.

Lukesh was undeterred, however, as he followed his interest in the built environment and applied to the Cal Poly architecture program. Cal Poly sat at the top of his list when it came to choosing a university education.

“When I got accepted, I was very excited because I know it’s a very impacted major and highly competitive,” Lukesh said.

At Cal Poly, Lukesh nurtured his love for architecture and decided to add a construction management minor. Under the mentorship of Cal Poly Professors Margo McDonald and Barry Williams, Lukesh became interested in environmental sustainability in design. During the summer, he interned at RRM Design Group based in San Luis Obispo and had the opportunity to take one of the very first LEED AP exams administered by the United States Green Building Council (USGBC), which he passed successfully.

As a fourth-year student, he studied abroad at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia, where he rigorously studied the integration of sustainability as part of the design and construction delivery process.

Lukesh’s interest and experience in sustainable building led him to the digital twin industry. Stints at companies like Webcor Builders, Regenerative Ventures, Integrated Environmental Solutions (IES) and Ernst & Young (EY) landed him at Gafcon Digital, a company entirely focused on creating and integrating digital twins throughout the digital building lifecycle.

Although digital twins are not a new concept, they are becoming increasingly common in new and existing buildings. A digital twin is a computerized virtual replica interactive model of a physical asset, such as the buildings in Lukesh’s work.

“Basically, how do we ensure that the buildings match the operational data of buildings [and] match the intended design? And then, over time, how do we optimize the asset’s operations to match that design for decarbonization and the impact on the environment? With time, buildings tend to lose performance. Leveraging the digital twin during operations allows facility managers and owner operators to identify problems before they become problems proactively preventing downtime in functionality and waste in cost,” he said.

Many building owners are unaware when a building is underperforming; digital twins can show when functions like lighting, ventilation, energy conservation measures (ECMs), and temperature units are not maintaining their optimal designed targets. The twin can also visualize, manage and maintain the entire operational system, making it much easier to proactively identify where maintenance is needed and make interventions to fine-tune long-term costs and efficiencies.

Building maintenance, like proper airflow, equipment optimization and adequate lighting, is important for cost-effectiveness, human health and reducing carbon footprint. Through his work, Lukesh made the connection between building efficiency and his journey dealing with seizures.

“I realized that the built environment had a potential impact on my seizure conditions, such as lighting, airflow dynamics, acoustics etc.,” he said.

In 2018, Lukesh unexplainably began experiencing uncontrollable seizures; some causing him to drown, ultimately leading to him losing his driver’s license. Some while on travels and within his work environments impacting his ability to successfully perform his job duties. Something needed to change, and a medical intervention was necessary.

The severity and increased frequency led Lukesh to a group of doctors at UCLA specializing in neurological and epileptic research. There, he endured several tests, including the Wada exam, which indicates to doctors which parts of the brain are important to speech, memory and vision functions.

Meanwhile, doctors were also collecting images and data to construct a digital twin of Lukesh’s brain.

“And so ultimately, just like we do with digital twins of buildings, you’re able to run all of these virtual and what-if scenarios before you actually make some sort of intervention,” he said. “In my case, an invasive surgical intervention was necessary.”

The digital twin allowed doctors to identify a possible remedy for Lukesh’s seizures: an RNS system. This process removes a part of his skull to access specific neural networks and implant an epilepsy device, NeuroPace that delivers personalized treatment by responding to abnormal brain activity and provides EEG data that can help improve patient care. It has a battery that connects to electrodes installed in the back of his head proactively preventing abnormal neural activity to prevent an epileptic condition.

Using his digital twin as a solution, neurologists can continuously monitor his brain performance and ensure the data trending maintains within a specific range of tolerance. When the performance trend goes beyond the range of tolerance, the electrodes send electrical “zaps” to the seizure’s origin point, proactively preventing the seizure before it happens.

Despite the surgery being invasive and the beginning of a long journey for Lukesh, his health has created a unique circumstance where his personal life and career passion intertwine. Having a digital twin of oneself, essentially, Lukesh has become a living representation of the technology he has so passionately worked to advance. A digital twin can prevent a seizure of an asset – either human operation or uptime in building functionality.

“I use this as a metaphorical use case of understanding how to optimize performance, an asset being a human or an asset being a building,” Lukesh said.

The goal is to change how humans and buildings interact with each other. Rather than having humans adapt to the buildings, Lukesh is focused on leveraging digital twin technologies to have buildings respond to the most expensive asset, humans, to optimize their conditions.

However, achieving complete building optimization is a process, as Lukesh explains by comparing it to his unwavering journey to being seizure-free.

“[NeuroPace] wasn’t just installed and then magically everything was solved. It was picking up and preventing about 90% of my seizures and proactively intervening them. But I’d still have some of these major breakthroughs,” Lukesh said, recalling a particularly critical doctor’s appointment.

He was increasingly frustrated with the frequency of his seizures despite having the neural device, which he expressed to his doctor. His doctor then pulled up his data from the last year and showed Lukesh the frequency and intensity of his seizures.

Although the data showed frequent breakthrough seizures over a year-long period, it also showed his brain activity stabilizing, meaning the electrodes fired less “zaps” as time went on. Not only did the data provide a sense of comfort that the treatment was working, but it also helped Lukesh realize something within his own work.

“The brain is like a muscle; it is a muscle. And what it’s doing is this device is forcing the brain to build new neural networks around the seizure origin points and scar tissue points so that the brain is continuously self-improving and optimizing itself,” he explained.

The battery does not stop all seizures, though it strengthens the brain to defend itself — a concept translated to buildings. Through Machine Learning (ML) and Artificial Intelligence (AI), the digital twin technology learns more about the building and its conditions, it becomes more effective in proactively identifying problem spots through Fault Detection and Diagnosis (FDD) and fixing them on its own just like his head’s digital twin.

“When we make a change in the digital twin of a building, it doesn’t necessarily mean it’s going to prevent the problems in the buildings right away,” Lukesh said. “It takes time, continuous data aggregation, simulation and calibration for a closed-loop analysis in order to strike the correct balance on optimizing the building’s functionality.”

Through his journey in both the building industry and medical sector — which act in separate silos — Lukesh has recognized the opportunity for technical cross-pollination.

For now, Lukesh is working to implement digital twin technology, digital building lifecycle and digital thread throughout the built environment. It’s an innovative step toward widespread building optimization and environmental sustainability — an issue where so many have looked for a miracle. In the case of Lukesh’s head, however, miracles can happen every day.

see Lukesh's presentation on "Integration of Human and Building Digital Twins"